POLYPHONIC SATAN

I am participating with a three-channel video installation in the exhibition “La Beauté du Diable” co-curated by Benjamin Bianciotto and Sylvie Zavatta for the Frac Franche-Comté in Besançon.

La Beauté du Diable

Frac Franche-Comté, Besançon, France

16.10.2022 – 12.03.2023

The exhibition, which was due to end on 12 March, has been extended until Sunday 14 May 2023.

With works by Renaud Auguste-Dormeuil, Béatrice Balcou, Valérie Belin, Bianca Bondi, Christine Borland, Gast Bouschet, Pascal Convert, Nicolas Daubanes, Stan Douglas ,Léon Ferrari, Marina Gadonneix, Douglas Gordon, Majd Abdel Hamid, Suzanne Husky, William Kentridge, Joachim Koester, Nino Laisné, Julien Langendorff, Élodie Lesourd, Robert Longo, David Mach, Myriam Mechita, Annette Messager, Patrick Neu, Eric Pougeau, Sophie Ristelhueber, Andres Serrano, Annelies Štrba, Iris Van Dongen, Jean-Luc Verna, Jérôme Zonder.

The installation focuses on the work I did in collaboration with the writer and dancer Alkistis Dimech.

Music is by Kevin Muhlen and Angelo Mangini.

Non serviam

Exhibiting my work in cultural institutions is always linked to a critical engagement with the way art is communicated and interacted with in these places. The will not to offend the supposed sensibilities of the general public increasingly tempt cultural institutions to defuse radical art and make it appear family-friendly. The Frac Besançon is just one example of many where this is happening. On their social media pages, the exhibitions always look kind of the same, more reminiscent of bright, tidy children’s rooms than places that reflect the gravitas of life and the threat of chaos that underlies authentic art. In the case of an exhibition about Satan, this is an unacceptable trivialisation.

In protest, and to restore the subversive potential of art, I suggested that the space containing our video installation be left open but empty, so that the dark energy that had accumulated in it over the five months of the exhibition could escape into the museum and infect the exhibition during its extension. The director of the Frac did not reply to my proposal, and the carefully conducted philosophical discussions and negotiations with the co-curator Benjamin Bianciotto, whom I consider a friend and ally, have nontheless ultimately resulted in my proposal failing. With the intervention, I wanted to critically question whether art has to be entertaining, positive or even just visible, especially in an exhibition that is supposed to deal with the devil. Or whether it cannot also be an expression of a politics of the invisible (i.e. the occult), of controversy and outrage.

Dissident forms of understanding art that defy institutional reason are doomed to fail in the art world, but at least my idea is now in the world and can continue to act as a potential for revolt. In a sense, a work of art exists as soon as it is conceived, and its subsequent execution or failure is primarily a testimony to political power relations.

The question that not only I have to ask myself is what role art institutions play in society and whether they are able to be a vehicle for radical art. Be that as it may, whoever is responsible for an exhibition on Satan should not disregard the possibility of opposition and rebellious confrontation. It is worthwhile to let the curators themselves have their say here, who write in their statement: “Taking their cue from Lucifer’s “non serviam” in a veritable song of revolt, the artists in turn refuse to allow themselves to be controlled by an authority considered unjust or arbitrary and to submit to fate.”

A photo published in the French press juxtaposes our installation with Andres Serrano’s Piss Satan.

La Beauté du Diable

“You gave me the mud and I turned it into gold”

Charles Baudelaire

Following on from the exhibition L’homme gris, presented at Casino Luxembourg by Benjamin Bianciotto, La Beauté du Diable proposes to explore the presence of Satan in contemporary art from the angle of his figuration and his metamorphoses. Beyond the representations explicitly referring to the Devil or his symbolism, the exhibition aims to question the aestheticization of Evil through works that transmute the “repulsive” into aesthetic pleasure. By questioning our certainties and confronting them with the structural resistance of Western societies, these works have an undeniable political dimension. They turn taste on its head: a transgressive alchemy of sorts. Taking their cue from Lucifer’s “non serviam” in a veritable song of revolt, the artists in turn refuse to allow themselves to be controlled by an authority considered unjust or arbitrary and to submit to fate. Lucifer is confused with Prometheus, and the ‘light-bearing’ angel bringing illumination and freedom to creators in a post-romantic and symbolist heritage. Through the double movement of unveiling the horrible (in the image of the Apocalypse, which means Revelation) and its revival in seductive garb, they seem to affirm their refusal of the pain and ugliness of the world. But the exhibition also questions the role and place of art in our current societies. Recent creation is perfectly aware that danger lurks beneath the attractive varnish; it too knows how to play on this ambiguity, disguising reality in order to better charm us, adorning itself with the trappings of capitalist and advertising perdition. Finally, The Devil’s Beauty will not evade the religious dimension, from the demonisation of contemporary art to its capacity to revive debate within secularised cultures. Ambivalent, polysemic and cathartic, the exhibition highlights the oxymoron contained in its very title, and assumes and defends this fascination with Faustian overtones.

– Curatorial statement.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus aims to explore what Alkistis Dimech calls “the dynamics of the occulted body” through a dance of darkness. And by darkness I mean the essence of chaos, which the alchemists call Satan. But “dance of darkness” is of course also the name that Tatsumi Hijikata gave to Ankoku Butoh, the transgressive art form that probably most influenced Alkistis in the elaboration of an intense choreography situated somewhere between sensual embodiments of inner landscapes and demonic transmutations. Through the expression of ambiguous beauty, the videos we present in the exhibition “La Beauté du Diable” merge satanic darkness with Luciferian light in a kind of alchemical wedding that gives birth to the Black Sun. The footage was recorded during two ritual dance performances that took place on the occasion of our exhibitions “Metamorphic Earth” and “Poison Oracle” and is set against the backdrop of images that we filmed during a total eclipse over the Arctic. The installation Phosphorus will premiere at Frac Franche-Comté.

– Gast Bouschet

Since the 1980s, Gast Bouschet, alone or in the company of Nadine Hilbert, has built up a body of work that deconstructs and dismantles power structures: those that govern socio-economic domination; those that, illusorily, grant a central place to man on Earth. While he favours immersive video installations, photography, painting and even intervention in the heart of the forest appear as expressive forms with similar stakes. Through a long, immense and elaborate alchemical and sorcerous work, the Luxembourg artist pursues a reflection on the mutations and metamorphoses of matter and images, on the creative destruction that defies finitude. In this sense, the notion of movement is central to his artistic vision. The video installation Phosphorus (2017-2022) was created in close collaboration with Alkistis Dimech, a ‘sabbatical dancer’, practising Ankoku Butoh with a clear awareness of its enigmatic, radical and magical scope. Faced with this invasion of light and darkness, of radiant reds, we take part in a transmutation played out on different levels: that of the “occulted” body, of the primordial Earth, of the interconnection of the two going as far as fusion. Reunited in an alchemical process, the bodies change without altering, the demonic interiority reaches its freedom, chaotic and luminous, the movement introduced by the dance revives the Luciferian thought and the deep rituals. The eclipse symbolically offers this essential passage, just as the multiplication of the dancer’s body makes explicit the physical, geological and psychological upheavals at work. We then witness the rise of Phosphorus, the “Morning Star”, which joins Venus to Lucifer.

– Benjamin Bianciotto

14.11.2020 — 6.6.2021

Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain

I participate with three pieces (1990, 2014, 2020) in an exhibition that Benjamin Bianciotto is curating for Casino Luxembourg.

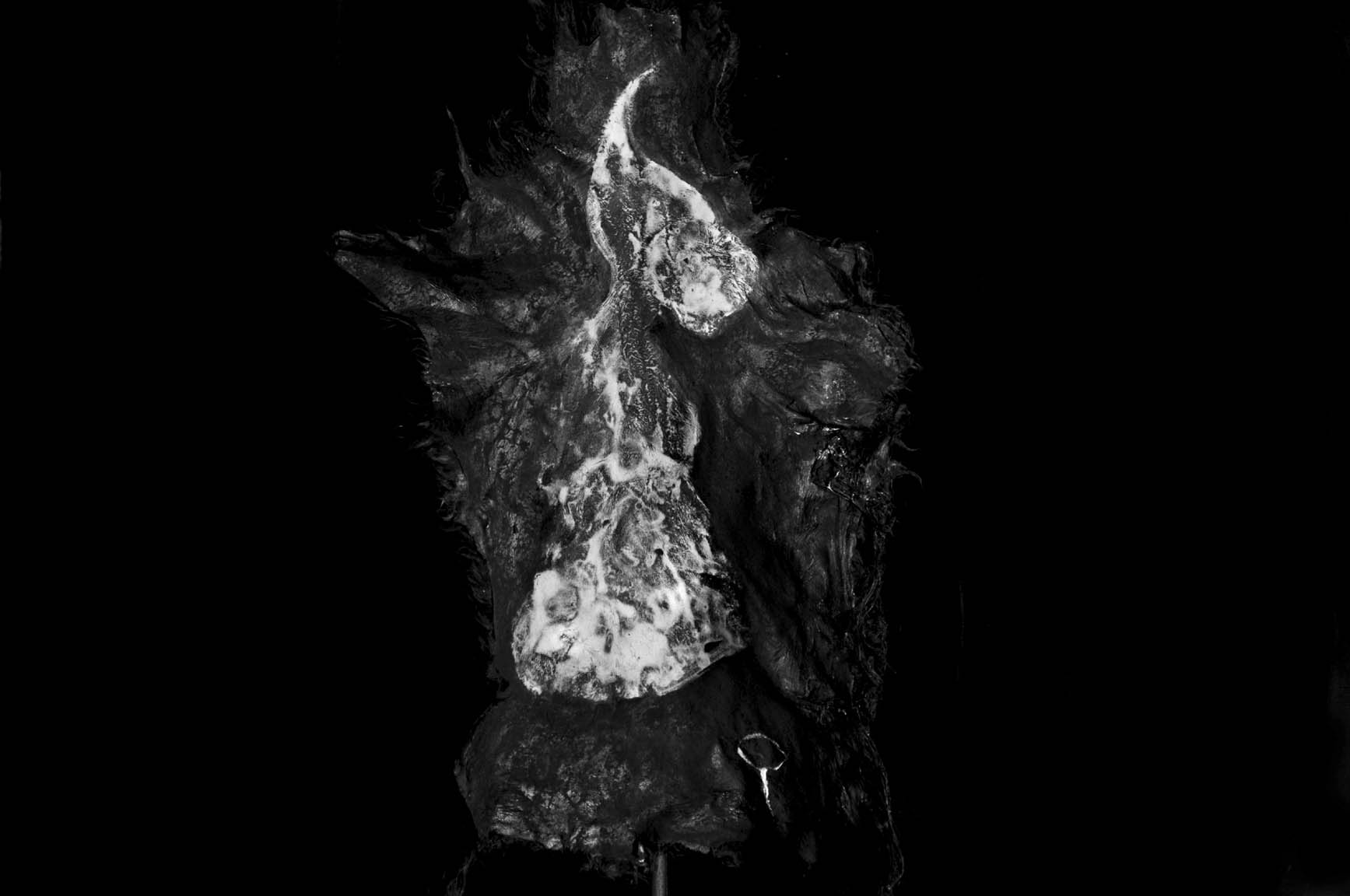

POLYPHONIC SATAN connects a series of camera-less photographs that fix the volatile movements of burning petrol on photosensitive paper, to a video of volcanic ashfall infiltrating glacial ice, and a painting made with obsidian powder on goatskin.

The exhibition L’HOMME GRIS deals with non-archetypal visions of the Devil, the way in which he slips away, changes, infiltrates, and becomes all the more dangerous, powerful, or liberating. The show evokes questions of internalization of evil in humans, anonymity, strategic concealment, the banality of crime, the underground, the mask, the visible/invisible, the mass, hidden or extinct flamboyance, etc. – thus crossing philosophical, economic, political, aesthetic, and moral poles.

L’homme gris – The finale: Les Sphères (effondrez-les)

w. Kali Malone & Stephen O’Malley

Sixth of June 2021

L’exposition L’homme gris interroge les représentations non archétypales du Diable dans l’art contemporain. Bien loin de disparaître, sa figure a simplement muté, démontrant de nouveau la fascinante faculté d’adaptation qui lui a permis de traverser l’histoire de l’art – et des hommes –, sans faiblir. Alors que la manière dont la figure du Diable s’éclipse, se transforme, s’infiltre lui permet de revendiquer une position d’autant plus dangereuse, puissante ou libératrice, elle offre aux artistes deux voies possibles à explorer. Leur choix oscille ainsi entre

la coquille vide, le costume à endosser, l’image pure, et une insaisissable et constante métamorphose. Cette stimulante alternative évoque, voire invoque, les dissimulations réflexives ou le recours à l’anonymat comme armes stratégiques ; révèle l’intériorisation maléfique en l’homme et son insoutenable banalité ; questionne la frontière du visible et de l’invisible, du déguisement et de la masse; aspire à raviver une ténébreuse flamboyance. La diagonale de la création traverse dès lors des pôles philosophiques, économiques, politiques, esthétiques ou moraux.

ARTISTS: ALEX BAG, DARJA BAJAGIC, CHRISTINE BORLAND, GAST BOUSCHET, CHRISTOPH BÜCHEL, SARAH CHARLESWORTH, JAN FABRE, IRENA HAIDUK, JOHN UHRO KEMP, RAGNAR KJARTANSSON, JULIEN LANGENDORFF, ELODIE LESOURD, TONY OURSLER, ANDRES SERRANO, SINDRE FOSS SKANCKE, DAVID TIBET, IRIS VAN DONGEN, GISÈLE VIENNE, MARNIE WEBER, JÉRÔME ZONDER

CURATOR: BENJAMIN BIANCIOTTO

https://www.casino-luxembourg.lu/en/Exhibitions/L-Homme-gris

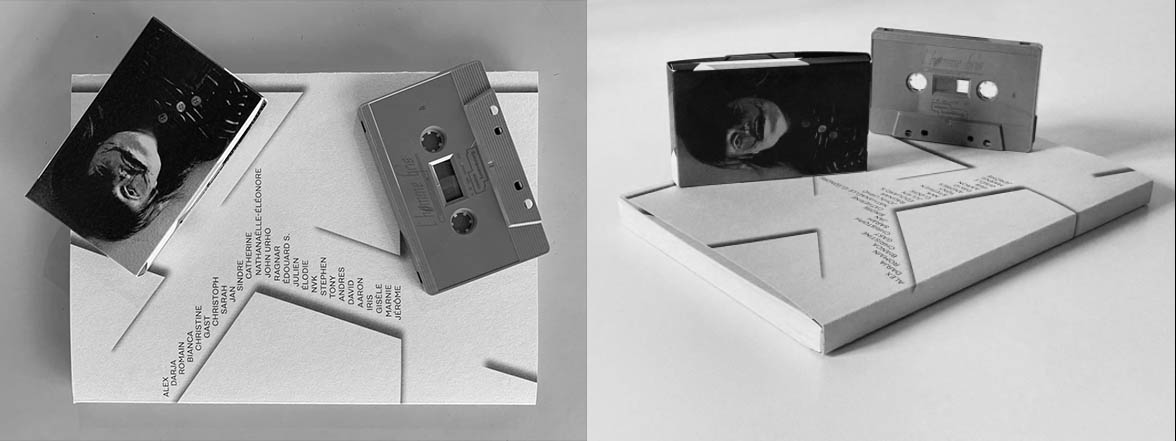

Book exploring individual relationships between the artists and the devil plus audiocassette containing 11 tracks all inspired by the works in the exhibition. With the contributions of

for publication:

Andres Serrano, Bianca Bondi, Catherine Guesde, Darja Bajagic, David Tibet, Elodie Lesourd, Gast Bouschet, Gisèle Vienne, Iris Van Dongen, Jan Fabre, Jerome Zonder, Julien Langendorff, Marnie Weber, Nathana ëlle-Eléonore Hauguel, Ragnar Kjartansson, Romain Barbot , Sindre Foss Skancke, Stephen O’Malley

for the tape:

Sa åad, Élodie Lesourd, Stephen O’Malley, NVK, Marnie Weber, Cigvë, Neuromancer, Julien Langendorff & Lori Sean Berg, Aaron Turner, Edouard S. Lamothe, Sindre Foss Skancke

Avatars du Malin

Une chance que ni les responsables du Casino, ni le commissaire Benjamin Bianciotto, ni les artistes n’aient été assez crédules pour succomber à ce que Baudelaire a appelé la plus belle ruse du Diable, de vous ou nous persuader qu’il n’existe pas. Il est vrai que le même Baudelaire nous a fournis par ailleurs la meilleure preuve de son existence, disant être bien obligé d’y croire, « car je le sens en moi ». Nous voilà avertis de mettre les pieds, fourchus ou non, dans l’exposition, intitulée L’Homme gris, et là, c’est une autre référence littéraire qui entre en jeu : le pauvre Peter Schlemihl, d’Adelbert von Chamisso, nous sommes en plein dans le fantastique romantique, qui a vendu son ombre. Il l’a fait à un personnage en habit gris, dissimulation habile du Diable, plongée dans l’anonymat, en échange d’une bourse magique inépuisable.

Attendez-vous donc à une longue et passionnante confrontation avec toutes sortes d’avatars du Malin, que vous font rencontrer une vingtaine d’artistes contemporains. Confrontation non moins, il faut le préciser de suite, avec une omniprésence diabolique sur toutes sortes de terrains, esthétique bien sûr, philosophique, moral, politique, économique. Mais avant de s’engager dans cette aventure, véritable descente aux enfers, il faut comme Dante le fait avec Virgile, un guide, et le visiteur fera bien – autrement il risque le papillonnage (bien insatisfaisant) ou pire, la noyade dans le Styx – de prendre son temps et de lire le dépliant avec le texte d’introduction (voire d’initiation) de Benjamin Bianciotto. Ainsi, muni d’un vadémécum, il n’aura pas de mal à saisir le dessein et le propos du commissaire, entrera le mieux possible dans les différentes propositions des artistes.

Si, la plupart du temps, on s’éloigne des représentations classiques, ou simplement habituelles, du Diable, on reste bien du côté de l’archétype dans les premiers pas. Dans l’escalier, pour commencer, où Doctor Fabre vient à la rencontre, les cornes bien rouges, ainsi qu’au bout de la salle où l’on débouche, avec Piss Satan, d’Andres Serrano, et son rougeoiement sulfureux où se devine même la fourche (accessoire bien connu en été au bord des routes du Tour de France). Associé habituellement aux bas-fonds, aux profondeurs, aux abymes, Satan, le voici accroché très haut, l’invocation vient remplacer l’évocation, au bout d’un chemin en bois zigzaguant pour lequel les menuisiers ont eu à se démener, poursuivons l’image, comme de beaux diables.

Fabre et Serrano sont les artistes les plus connus, vivent les découvertes qui suivent, dans les techniques les plus diverses. Dans le dépliant, Benjamin Bianciotto, auteur d’une thèse en histoire de l’art sur les « Figures de Satan », l’exposition en est comme une mise en espace, a une phrase ou deux sur chacun(e) des artistes, sur leur contribution. On aura du mal en rendant compte de l’exposition à aller vers quelque chose de synthétique, à part d’insister sur le côté bien répandu du Diable, qui dès l’étymologie grecque est celui qui divise, désunit, détruit. Que de préfixes négatifs, alors qu’il n’est pas faux non plus de lui faire assumer un autre rôle, d’initiateur, de libérateur. De même, la diablesse, peu présente, étrangement absente, peut être femme méchante, acariâtre, ou petite fille turbulente et espiègle.

Satan is Real, Ragnar Kjartansson s’époumone à s’en faire le chantre, alors que la plupart des artistes obligent à y aller voir de plus près. Et l’aménagement, à tels endroits, exige même qu’on se penche sur les papiers, ailleurs les images restent plus directes, s’imposent avec de la force, de la persuasion. Les murs recouverts de papiers peints, l’un japonisant, d’Iris Van Dongen, l’autre carrément géométrique, suggérant l’Infinite Fall, d’Elodie Lesourd, s’avèrent des parenthèses entre lesquelles reposent par exemple les poupées de Gisèle Vienne, et un autre mur, au milieu, voit s’animer le feu, s’écouler l’eau et la lave d’un lac dégelé, de Gast Bouschet, de part et d’autre d’une peau de bouc peinte, l’animal est habituel des sabbats de sorcières.

Il appartient au visiteur d’approfondir telles étapes, à son choix, du parcours, de s’arrêter çà et là plus longtemps, peut-être à des choses moins spectaculaires, comme les encres de Chine de Jan Fabre, des masques qui conviennent à nos temps maussades, dont on suivra volontiers le commissaire dans son rapprochement du Sacrum, des vertèbres sacrées ou sacrales, et du Sacré justement. Si le titre de l’exposition relègue le Diable dans une grisaille anonyme, le voici qui célèbre le bas et le haut, réunit le corps et l’esprit. Et que dire des trois bouquets de fleurs, de Bianca Bondi, natures mortes sous cloche, pour quel salut luciférien qu’on peut imaginer adressé à l’autre versant de la vallée. L’ironie, de la sorte, ne devrait pas être la moindre compagne dans la visite de cette exposition, elle s’étale dans le regard.

L’Homme gris, une exposition qui se présente jusqu’au 31 janvier (si le diable de virus ne nous joue pas un mauvais tour de plus) comme une ample scène de théâtre, où le Malin endosse tant de rôles les uns à la suite des autres. La vie, si le visiteur y consent, en devient comme un songe, où le Tentateur fait se joindre définitivement le réel et l’imaginaire.

Lucien Kayser, d’Lëtzebuerger Land