WHEN BIRDS FLY AWAY

WHERE DOES GRIEF GO?

A Dark Shamanic Practice for Dark Ecological Times.

This short five-part survey of contemporary shamanic art looks at interaction rituals, particularly in relation to the birds of the Ardennes, a third of which are currently threatened with extinction and the situation continues to deteriorate. I will explore whether contemporary art that emerges from a creative encounter across species boundaries can be labelled ‘shamanic’ in a European context and what purpose it can fulfil.

Part One.

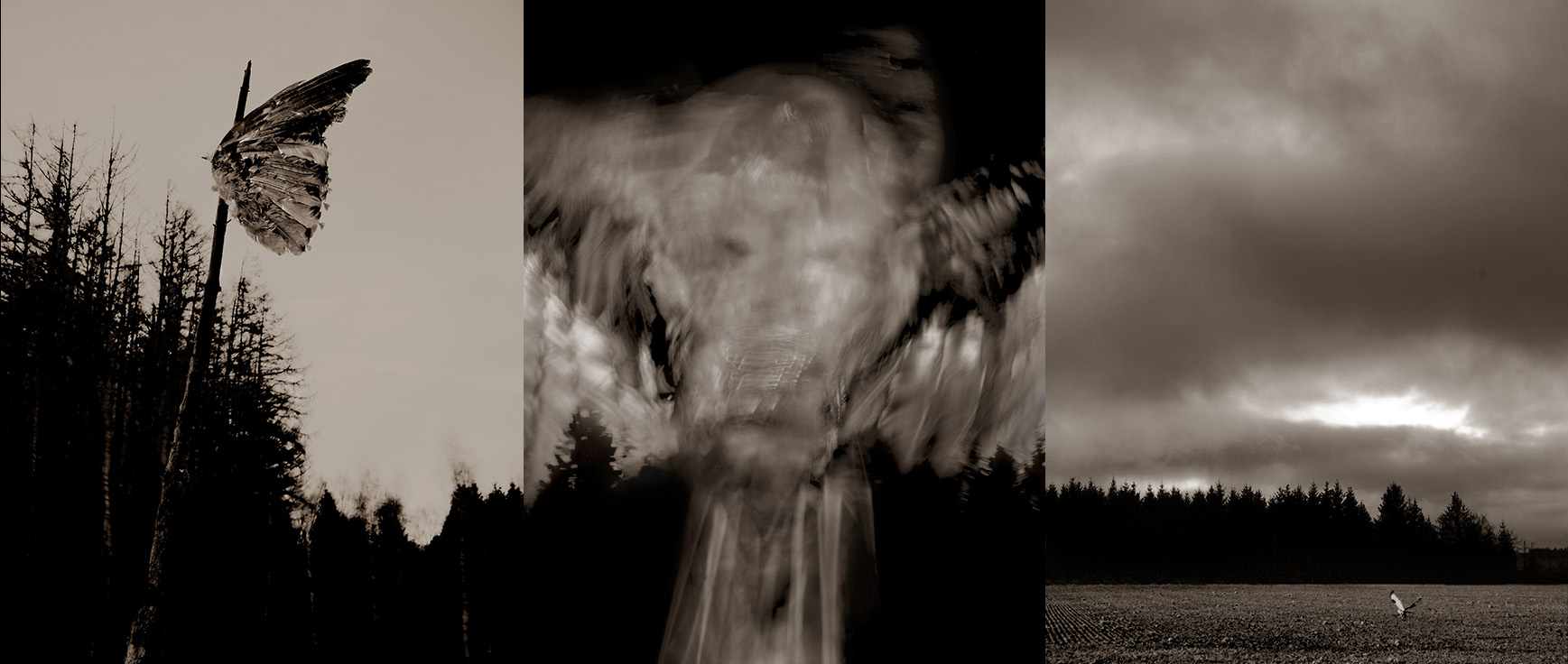

The production of an artefact like the one shown here takes a considerable amount of time and involves several steps. The first involved closely observing the scavengers as they ate the head and paws of a chicken that had just been slaughtered by friends on a neighbouring farm. This process was essential for establishing a deep connection with the base matter underlying the sculptural work.

After this outer and inner nigredo, I created something new by fusing the remains of the farm bird with those of a dead crow (i.e. a wild bird) and other materia magica. The resulting sculpture in some ways resembles what is called an ‘empowered cadaver’ in African Vodun, although I took it more literally than what is usually involved in the making of bocios, as Vodun sculptures are called. But I see this piece as primarily European, or even specific to the Ardennes, as it is linked to local economies and ecosystems and draws its strength from birds that have lived and died here.

Whatever the term ‘shamanism’ means exactly, now that it has moved away from its Siberian roots, if we want to apply it to our work, it must take into account our current living conditions. We do not live in an unspoilt wilderness, but in damaged ecosystems, and our so-called power animals are dependent on human regulation and threatened with extinction. I am sceptical that what has been damaged can be healed as long as the human population and its consumption continue to grow. And I shudder at the grim prediction that human activity may one day leave chickens the only birds on Earth. Still, I think shamanic art can play a role in our times by empowering the soul to transgress ecological grief and fear, and by building new connections between inner and outer nature.

Part Two.

The ritual wearing of a mask is less about hiding one’s appearance or being seen as someone else, and more about seeing through the eyes of the other. This alone justifies a contemporary shamanic practice, as it journeys us out of the human perspective. In our everyday busyness, we forget that there are as many views of the world as there are species or even animal persons.

Wearing the mask overlays our human nature with our animal nature and merges the two into a unified consciousness. As a result, we see the surroundings with different eyes, in my case the Ardennes forest and its edges, which provide ideal hunting grounds for the resident birds of prey. From such an ecstatic superimposition of realities arises the possibility of developing a lasting sense of intimacy, both with the animals that live with us and with our own animal-ness, which allows us to enter into a kinship with them, as tribal cultures do by making animals, often birds, their totem.

To animate a mask, it is useful to smear its inside with animal and human blood. This facilitates both the mutual attraction and the lighting of the inner fire that we need for the ritual work. It is a perilous affair* for more than one reason and requires an art that has little in common with what we normally associate with the art we see in museums and galleries. Most of the art exhibited there leaves us stuck on its aesthetic surface. Shamanic art is not what we understand by ‘fine art’. Its purpose is not to please the eye through masterful drawing techniques or the ability to create exquisite objects. Rather, it draws its power from the formative and destructive processes of nature, channelling them so that they invade images and sculptures and then, through their contemplation and handling, enter the mind, where they effect change.

* Coincidence or not, many years ago a fire broke out one night after some ritual work with a mask and I woke up the next morning in a toxic cloud that left me coughing up black phlegm for days. I’ve been careful ever since.

Part Three.

The ritual tool shown here, which I carved and then painted with buzzard excrement, initiated the flight to the nadir of the year. Spiderwebs hang from it to bind the demonic forces that accompany the journey into the underworld, both that of the forest and our own, to retrieve our animal soul trapped deep within. The confrontation with our own animality is characterised by ambivalence, because we only possess it if it also possesses us. Nevertheless, it is essential if we want to lead an authentic occult life.

Since Darwin’s study of human evolution, we know that we have been animals much longer than humans. However, we cannot commune with our animal ancestors, who are still buried in our bodies, through scientific means. Rather, this requires what Eliade called ‘archaic techniques of ecstasy’. And this is where the manipulation of sacred objects comes into play, as they enable the exchange of power and the transfer of transformative energy between our human and animal natures. In such borderline experiences, the mind shifts from a verbal to a visual level, so that we think with images, which is essential both for making sense of the visions we encounter on our infernal journeys and for creating this kind of art.

The key to visual thinking lies in association, juxtaposition and superposition. Shamanic thinking is characterised by the fact that the more similar things are, the more interchangeable they are. And if we can put them in a state of excitement and make them resonate with each other, we can transform one into the other. Shamanic kinship is not defined by the biochemical compositions that science uses to categorise the natural world, but by mutual attraction.

Engaging with our nonhuman otherness in an embodied sense and opening our bodies, or rather being opened by the other, results in the loss of our stable identity. However, this process allows for intimate relationships. Making shamanic art is like making love: it touches the deepest part of us, expands our sense of self and enables the transmission of emotions between those who participate in it.

Part Four.

Totemic wooden objects retain a connection to the forest from which they come. They carry the memory of the mother trees that pass on their heritage, of the drought of exceptionally warm summers that threatened their survival, of the sap that flows to the roots in autumn, of their interaction with the mycelium, of the soil that holds the trees in place, of the minerals that nourish the soil. They also carry the geological memory of the ground and the catastrophic events that have shaped and traumatised it, the stored experiences of the microbial, plant and animal life that has walked on that ground, the birds that perched on their branches, the air that has carried them and the storm that has raged through the canopy. All this makes up the forestial memory and that of the sculptures created from it.

Sometimes I work the wood more or less. In the case of the piece shown here, which occupies a central place in my shrine, it has hardly been worked at all. I think the less a totem deviates from its original appearance as a tree, the more it acts as its mediator. And of course I don’t seal a wooden sculpture so as not to silence its oracular voice.

Perhaps the daily communication and touching of the shrine, which carries the essence of forest, contributes to what Lévy-Bruhl called ‘participation mystique’. The intense relationship with a sacred object that allows it to be experienced as a complex form of life in itself. I could warm-up to that idea if we could free it from its paternalistic view of the ‘primitive psyche’. But we would probably be better off focussing on what lies ahead.

What matters today is the development of a way of thinking and feeling in which human subjectivity is a part, but not the dominant principle. My ritual work is in many ways about breaking chains, those of Anarch*, entrapped beneath the world system, but also the ideological chains that keep us trapped in the belief that human nature is separate from nature as such. Ultimately, it is about revealing our most authentic inner being and creating new forms of solidarity and a shared politics of the earth.

*As readers of my book of the same name, published by Scarlet Imprint, will know, working with Anarch is a central concern of mine. Not only, but also because of the paradox that Milton introduced into the term in ‘Paradise Lost’ when he combined ‘monarch’ with ‘anarchy’. He was expressing the fusion of the natural kingdom with its underlying principle of chaos. Nature is anarchic and yet organised. But it is a horizontal organisation in which no power is exercised from above. The artworks shown here feed on the primordial dark sacredness of matter, the pagan graininess embodied in mythological tales as the ancient gods who were defeated and banished to the underworld by monotheistic religions and later by modernity. They must endure chained there until the fabric of the world realigns in such a way that they can be freed by the sorcerous intervention of their accomplices on earth and regain their original power over world events. In such a revolutionary narrative, the activities of sorcerers and shamanic practitioners overlap, which is rare, as the shaman is usually seen as the sorcerer’s opponent in traditional animistic societies. In this case, however, they are not working against each other, as both practices aim to rid the world of its current ills.

Part Five.

Contemporary shamanic art enables liminal experiences in the undead landscapes of what has recently been called the anthropo-obscene. We should not be afraid to call this black shamanism, for it expresses the poisoning of the planet and the extinction of a multitude of species, perhaps including our own. Our shamanic task is to merge the horror with the wonder, and to transmute the

poison into an elixir that leads us to radically reinvent our selves and our role on earth.

I don’t presume to prescribe any particular way of doing this, but I also don’t want to hide what I think is desirable. Take it for what it is: an experience-driven approach to dealing with the mess we’ve gotten ourselves into. I am not saying that what I am proposing will save us, but it will prevent us from drowning in the shame of giving up without trying to embody change.

Let’s build the dream of an interspecies community based on ecological equality. Let’s challenge the rules that maintain hierarchies, even between species. Such work will make us outsiders, but shamanic practitioners have always impacted their cultures from the margins. The question is whether our culture recognises the need for visionary practices that inspire bold political action. And whether we will be able to draw strength and ancient resilience from adversity. If we want art to be part of the solution and not part of the problem, we need to free it from its entanglement with capital and build our own cultural ecosystem based on a passionate engagement with nature, no matter how damaged or hostile it is or will become.

Let’s fight the cancer of the human soul with assault sorcery. Let’s practice mystical anarchism, a mysticism without a divine ruler. Let’s journey into realms where we experience our innermost self as that which is primal and darkly sacred. From such a deep connection, a new identity will emerge that is no longer just that of homo sapiens, but embodies multiple natures simultaneously. Well then, soul, take flight with the birds and heal. Who would have thought that my black shamanic story would become a healing story after all?

Gast Bouschet, 14th January 2025.